Serving with Purpose: Lessons Learned from Consulting in Assessment and Research

Serving with Purpose: Lessons Learned from Consulting in Assessment and Research

By Jerri Berry Danso

I’m Jerri Berry Danso, a first-year doctoral student in the Evaluation, Statistics, and Methodology (ESM) program at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville. Before beginning this new chapter, I spent over a decade working in higher education assessment: first as the Director of Assessment for the College of Pharmacy at the University of Florida, and later in Student Affairs Assessment and Research. During those years I learned how purposeful data work can illuminate student learning, sharpen strategic planning, and strengthen institutional effectiveness. Across these roles, I collaborated with faculty, staff, and administrators on a wide range of projects, where I supported outcomes assessment, research design, program evaluation, and data storytelling.

Whether it was designing a survey for a student services office or facilitating a department’s learning outcomes retreat, I found myself consistently in the role of consultant: a partner and guide, helping others make sense of data and translate it into action. Consulting, I’ve learned, is not just about expertise; it also requires curiosity, humility, and a service mindset. And like all forms of service, it is most impactful when done with purpose. My goal in this post is to share the values and lessons that shape my approach so you can adapt them to your own practice.

What Does It Mean to Consult?

In our field, we often engage in informal consulting more than we realize. Consulting, at its core, is the act of offering expertise and guidance to help others solve problems or make informed decisions. In the context of research, evaluation, assessment, and methodology, this can involve interpreting data, advising on survey design, facilitating program evaluation, or co-creating strategies for data-informed improvement.

I define consulting not only by what we do, but also by how we do it – through relationships built on trust, clarity, and mutual respect. If you’ve ever had someone turn to you for guidance on a research or assessment issue because of your experience, congratulations! You’ve already engaged in consulting.

My Core Consulting Values

My foundation as a consultant is rooted in an early lesson from graduate school. While earning my first master’s degree in Student Personnel in Higher Education, I took a counseling skills course that fundamentally shaped how I interact with others. We were taught a core set of helping behaviors: active listening, empathy, reflection, open-ended questioning, and attention to nonverbal cues. Though designed for future student affairs professionals, these skills have served me equally well in consulting settings.

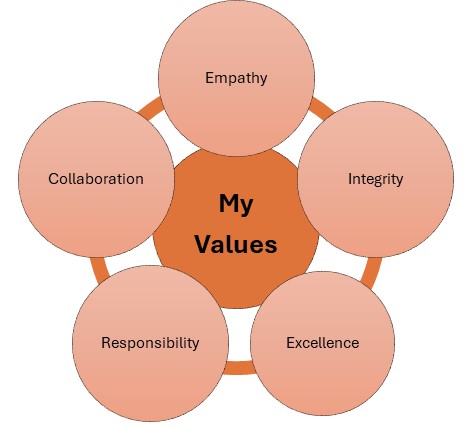

From that experience, and years of practice, my personal consulting values have emerged:

- Empathy: Understanding what matters to the client, listening deeply, and genuinely caring about their goals.

- Integrity: Being transparent, honest, and grounded in ethical principles, especially when working with data.

- Collaboration: Co-creating solutions with clients and recognizing that we are partners, not saviors.

- Responsibility: Taking ownership of work, meeting commitments, and communicating clearly when plans change.

- Excellence: Striving for quality in both process and product, whether that product is a report, a workshop, or a relationship.

These values are my compass. They help me navigate difficult decisions, maintain consistency, and most importantly, deliver service that is thoughtful and human-centered.

Lessons from the Field

Over the years, I’ve learned that the best consultants don’t just deliver technical expertise. They cultivate trust. Here are a few key lessons that have stuck with me:

- Follow through on your promises. If you say you’ll deliver something by a certain date, do it, or communicate early if something changes. Reliability builds credibility and fosters trust in professional relationships.

- Set expectations early. Clarify what you will provide and what you need from your client to be successful. Unmet expectations often stem from assumptions left unspoken.

- Stick to your values. Never compromise your integrity. For example, a client asked me to “spin” data to present their program in a more favorable light. I gently reminded them that our role was to find truth, not polish it, and that honest data helps us improve.

- Anticipate needs. When appropriate, go a step beyond the request. In one project, I created a detailed methodology plan for a project that the client hadn’t asked for. They later told me it became a key reference tool throughout the project.

- Adapt your communication. Know your audience. Avoid overwhelming clients with technical jargon, but don’t oversimplify in a way that’s condescending. Ask questions, check for understanding, and create space for curiosity without judgment.

The Art of Service

Good consulting is about more than solving problems; it is equally about how you show up for others. What I’ve come to call the art of service is an intentional approach to client relationships grounded in care, curiosity, and a commitment to helping others thrive. This includes:

- Practicing empathy and active listening

- Personalizing communication and building rapport

- Going beyond what’s expected when it adds value

- Continuously reflecting on your approach and improving your craft

These principles align closely with literature on counseling and helping relationships. For instance, Carl Rogers (1951) emphasized the power of empathy, congruence, and unconditional positive regard. These are qualities that, when applied in consulting, build trust and facilitate honest conversations. Gerald Egan (2014), in The Skilled Helper, also highlights how intentional listening and support lead to more effective outcomes.

A Call to Aspiring Consultants

You don’t need consultant in your job title to serve others through your expertise. Whether you’re a graduate student, an analyst, or a faculty member, you can bring consulting values into your work, especially in the measurement, assessment, evaluation, and statistics fields, where collaboration and service are central to our mission.

So, here’s my invitation to you:

Take some time to define your own values. Reflect on how you show up in service to others. Practice listening more deeply, communicating more clearly, and delivering with care. The technical side of our work is vital, but the human side? That’s where transformation happens.

Resources for Further Reading

- Egan, G. (2014). The Skilled Helper: A Problem-Management and Opportunity-Development Approach to Helping (10th ed.). Cengage Learning.

- Rogers, C. R. (1951). Client-Centered Therapy: Its Current Practice, Implications and Theory. Houghton Mifflin.

- Block, P. (2011). Flawless Consulting: A Guide to Getting Your Expertise Used (3rd ed.). Wiley.

- Kegan, R., & Lahey, L. L. (2016). An Everyone Culture: Becoming a Deliberately Developmental Organization. Harvard Business Review Press.