Timing is Everything… Or Is It? How Do We Incentivize Survey Participation?

Timing is Everything… Or Is It? How Do We Incentivize Survey Participation?

By M. Andrew Young

Hello! My name is M. Andrew Young. I am a second-year Ph.D. student in the Evaluation, Statistics, and Methodology Ph.D. program here at UT-Knoxville. I currently work in higher education assessment as a Director of Assessment at East Tennessee State University’s college of Pharmacy.

Let me tell you a story; and you are the main character!

4:18pm Friday Afternoon:

Aaaaaand *send*.

You put the finishing touches on your email. You’ve had a busy, but productive day. Your phone buzzes. You reach down to the desk and turn on the screen to see a message from your friends you haven’t seen in a while.

Tonight still good?

“Oh no! I forgot!” You tell yourself as you flop back in your office chair. “I was supposed to bring some drinks and a snack to their house tonight.”

As it stands – you have nothing.

You look down at your phone while you recline in your office chair, searching for “grocery stores near me.” You find the nearest result and bookmark it for later. You have a lot left to do, and right now, you can’t be bothered.

Yes! I am super excited! When is everyone arriving? You type hurriedly in your messaging app and hit send.

You can’t really focus on anything else. One minute passes by and your phone lights up again with the notification of a received text message.

Everyone is getting here around 6. See you soon!

Thanks! Looking forward to it!

You lay your phone down and dive back into your work.

4:53pm:

Work is finally wrapped up. You pack your laptop into your backpack, grab a stack of papers, joggle them on your desk to get them at least a little orderly before you jam them in the backpack. You shut your door and rush to your vehicle. You start your car, navigate to the grocery store you bookmarked earlier.

“17 minutes to your destination,” your GPS says.

5:12pm:

It took two extra minutes to arrive because, as usual, you caught the stoplights on the wrong rotation. You finally find a parking spot, shuffle out of your car and head toward the entrance.

You freeze for a moment. You see them.

You’ve seen them many times, and you always try to avoid them. You know there is going to be the awkward interaction of a greeting, a request of some sort; usually for money. Your best course of action is to ignore them. Everyone knows that you hear them, but it is a small price to pay in your hurry.

Sure enough, “Hello! Can you take three minutes of your time to answer a survey? We’ll give you a free t-shirt for your time!”

You shoot them a half smile and a glance as you pick up your pace and rush past the pop-up canopy and table stacked with items you barely pay attention to as you pass.

Shopping takes longer than you’d hoped. The lines are long at this time of day. You don’t have much, just an armful of goods, but no matter, you must wait your turn. Soon, you make your way out of the store to be unceremoniously accosted again.

5:32pm:

You have to drive across town. Now, you won’t even have enough time to go home and change before your dinner engagement. You rush towards the door. The sliding doors part as you pass through the entrance, right by them.

“Please! If you will take three minutes, we will give you a T-shirt. We really want your opinion on an important matter in your community!”

You gesture with your hand and explain, “I’m sorry, but I’m in a terrible rush!”

——————————————————————————————–

So, what went wrong for the survey researchers? Why didn’t you answer the survey? They were at the same place at the same time as you. They offered you an incentive to participate. They specified that it was only going to take three minutes of your time to complete. So, why did you brush them off as you have many other charities and survey givers in the past situated in front of your store of choice?

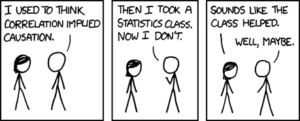

Oftentimes, we are asked for our input, or our charity, but before we even receive the first invitation, we have already determined that we will not participate. Why? In this scenario, you were in a hurry. The incentive they were offering was not motivating to you.

Would it have changed your willingness to participate if they offered a $10 gift card to the store you were visiting? Maybe, maybe not.

The question is, more and more, how do we incentivize participation in a survey? Paper, online, person-to-person. They are all suffering by the conundrum of falling response rates (Lindgren et al., 2020). This impacts the validity of your research study. How can you ensure that you are getting heterogeneous sampling from populations? How can you be sure that you are getting the data you need from the people you want to sample? This can be a challenge.

In recent published works on survey incentives, many studies acknowledge that time and place affects participation, but we don’t quite understand how. Some studies, such as Lindgren et al. (2020), have tried to determine the time of day and day of week to invite survey participants, but they themselves discuss the limitations in their study, which is endemic to many studies, which is the lack of heterogeneity of participants and the interplay of response and nonresponse bias:

While previous studies provide important empirical insights into the largely understudied role of timing effects in web surveys, there are several reasons why more research on this topic is needed. First, the results from previous studies are inconclusive regarding whether the timing of the invitation e-mails matter in web survey modes (Lewis & Hess, 2017, p. 354). Secondly, existing studies on timing effects in web surveys have mainly been conducted in an American context, with individuals from specific job sectors (where at least some can be suspected to work irregular hours and have continuous access to the Internet). This makes research in other contexts than the American, and with more diverse samples of individuals, warranted (Lewis & Hess, 2017, p. 361; Sauermann & Roach, 2013, p. 284). Thirdly, only the Lewis and Hess (2017), Sauermann and Roach (2013), and Zheng (2011) studies are recent enough to provide dependable information to today’s web survey practitioners, due to the significant, and rapid changes in online behavior the past decades. (p. 228)

Timing, place/environment, and matching the incentive to the situation and participant (and maybe even topic, if possible) is influential in improving response rates. Best practices indicate that pilot testing survey items can help create a better survey, but how about finding what motivates your target population to even agree to begin the survey in the first place? That is less explored, and I think is an opportunity for further study.

This gets even harder when you are trying to reach hard-to-reach populations. Many times, it takes a variety of approaches, but what is less understood, is how to decide on your initial approach. The challenge that other studies have run into, and something that I think will continue to present itself as a hurdle is this: because of the lack of research on timing and location, and because of the lack of heterogeneity in the studies that do exist, the generalizability of studies is limited, if not altogether impractical. So, that leads me full-circle back to pilot-testing incentives and timing for surveys. Get to know your audience!

Cool Citations to Read:

Guillory, J., Wiant, K. F., Farrelly, M., Fiacco, L., Alam, I., Hoffman, L., Crankshaw, E., Delahanty, J., & Alexander, T. N. (2018). Recruiting Hard-to-Reach Populations for Survey Research: Using Facebook and Instagram Advertisements and In-Person Intercept in LGBT Bars and Nightclubs to Recruit LGBT Young Adults. J Med Internet Res, 20(6), e197. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.9461

Lindgren, E., Markstedt, E., Martinsson, J., & Andreasson, M. (2020). Invitation Timing and Participation Rates in Online Panels: Findings From Two Survey Experiments. Social Science Computer Review, 38(2), 225–244. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439318810387

Robinson, S. B., & Leonard, K. F. (2018). Designing Quality Survey Questions. SAGE Publications, Inc. [This is our required book in Survey Research!]

Smith, E., Loftin, R., Murphy-Hill, E., Bird, C., & Zimmermann, T. (2013). Improving developer participation rates in surveys. 2013 6th International Workshop on Cooperative and Human Aspects of Software Engineering (CHASE), 89–92. https://doi.org/10.1109/CHASE.2013.6614738

Smith, N. A., Sabat, I. E., Martinez, L. R., Weaver, K., & Xu, S. (2015). A Convenient Solution: Using MTurk To Sample From Hard-To-Reach Populations. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 8(2), 220–228. https://doi.org/10.1017/iop.2015.29

Neat Websites to Peek At:

https://blog.hubspot.com/service/best-time-send-survey (limitations, again, no demographics understanding, they did say to not send it in high-volume work times, but not everyone works the same type of M-F 8:00am-4:30pm job)

https://globalhealthsciences.ucsf.edu/sites/globalhealthsciences.ucsf.edu/files/tls-res-guide-2nd-edition.pdf (this is targeted directly towards certain segments of hard-to-reach populations. Again, generalizability challenges, but the idea is there)

Hello! My name is Kiley Compton and I am a fourth-year doctoral student in UT’s

Hello! My name is Kiley Compton and I am a fourth-year doctoral student in UT’s

By M. Andrew Young

By M. Andrew Young